Fantasy or Fantastic Real Estate

By Linda Lee —

PART I

It’s called the Playhouse. For more than 100 years it has been in the hands of only two families: the Woodhouses and the Brockmans. Now there will be a third owner. People think of the Playhouse as a Tudor Great Hall, and may have a hard time imagining what life would be like living in that era. But how about “Downton Abbey”? Because that was the time in which this place was built.

Downton Abbey was set between 1912, before the Great War, through the Roaring Twenties, up to the Great Depression. In 1916 the Woodhouses, a rich American family, built their fantasy of a British great hall on a pastoral piece of property smack in the middle of East Hampton. And it was a lively place for their daughter through the 1920s.

The current owners are the psychiatrist, playwright and Columbia University professor Richard Brockman and his wife, Mirra Bank, a documentary filmmaker. Prof. Brockman inherited the Playhouse from his father, who was a passionate supporter of the arts.

Of course it has been modernized. Today it has five bedrooms, five baths, a modern kitchen and a pool. The price is $17.5 million.

The modernized kitchen at 64 Huntting Lane (Building photos, Sotheby’s International)

But it is also a protected East Hampton historic property. Sorry. You can’t tear it down and build mansions on the nearly three-acre lot. And unless you go in front of the town board and change the zoning (unlikely) you can’t turn it into a luxury BnB. It is in a residential area on Huntting Lane.

You can’t change the exterior. But just as all those twee Brits want to go to someone’s country pile for a weekend, anyone would be delighted to be a weekend guest here. There is that pool. It’s not far from Main Beach. The center of East Hampton is just a walk away. The Palms is practically around the corner.

This is for someone who wants to live in another person’s fantasy. Cindy Shea, one of two people at Sotheby’s International Bridgehampton who have the exclusive listing, says, “It’s like you’re in Europe. I feel like I’m in King Arthur’s period when I walk in.”

The 75-foot-long Great Room. In Elizabethan times a hall like this was used for ceremonies, dinners, processions, announcements, trials, and, by spreading grass and rushes on the floor, sleeping quarters for visiting servants.

Lorenzo Easton Woodhouse was president of the Merchants National Bank of Burlington, Vt. He and his wife, Mary Kennedy Woodhouse, had a large house in Burlington. But they also had an apartment at 66th and Park Avenue. (His wealth came, laterally, from Marshall Fields in Chicago.) Then they decided to build a cottage in East Hampton, next to Greycroft, his uncle’s house, now owned by Alan and Susan Patricof.

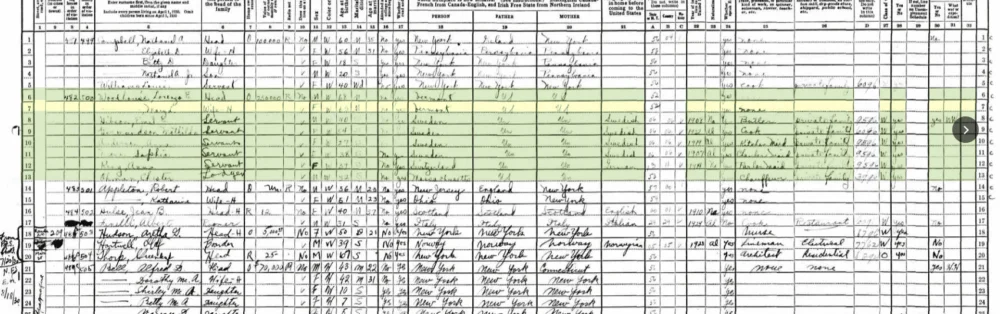

They called their house the Fens. In the 1930 census it was valued as being worth $250,000. The Playhouse was, of course, counted as part of the property.

The 1930 Census shows the Woodhouses living in East Hampton. The servants listed are: butler, cook, kitchen maid, chamber maid, parlor maid, and chauffeur.

They built the Playhouse in 1916 as a gift for their daughter, Marjorie, to fulfill her dreams of becoming an actress. (According to records, Marjorie was born in Vermont in 1902, so she was 14.) Here she could have her own stage, bring in her friends, put on entertainments. She probably invited friends from “the city,” where she apparently was attending school.

The architect for the Playhouse was Francis Burrall Hoffman Jr., fresh off his work on the baroque mansion Vizcaya in Florida, now a museum.

Ah, the rich. Some girls want a pony, which is much smaller and easier to sell.

If Marjorie had been a raving beauty — she was not — this might have been a movie.

This highly flattering portrait of Marjorie Woodhouse is by William J. Whittemore; it is held by, of course, Guild Hall

Marjorie married first Frederic William Procter, you know, Proctor & Gamble. They had two children, first Frederic William Procter, Jr., born five months after her wedding in the Great Room, age 19. Patricia Marise Procter (the spelling of the family name “Procter/Proctor” changed, along with the success of the brand) was born two years later, with congenital defects that led to a long stay in a hospital in New York where she had a series of orthopedic surgeries.

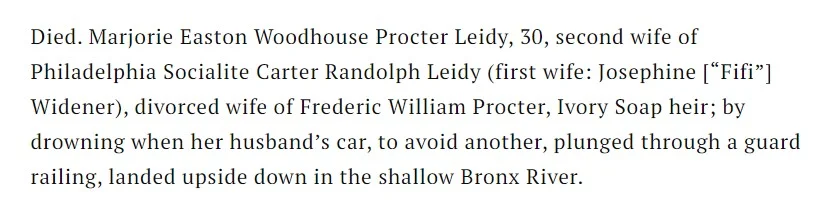

By then Marjorie was off to Paris — the Reno of the 1920s — t0 get a divorce. (So many court cases. Darren Star, are you listening?) Soon Marjorie Woodhouse Proctor met Carter Leidy, a handsome Philadelphian who had been married to “Fifi” Widener — of the Widener Library family — but was now on the loose.

Marjorie and Carter Leidy in Rye, NY. Such photographic evidence makes you wonder what royal subjects might really have looked like when Holbein painted them.

They married, but it did not please her parents. In fact, the marriage was kept secret from the Woodhouses for a while. Mrs. Leidy did see her son and daughter again. In the 1930 census the Leidy household on Captain’s Lane in Rye, New York, had three children, her son and daughter from her first marriage and a baby of a year and a half. Another baby would come along in the next two years. Luckily she had four servants on hand to help. Her husband was a steel salesman. Homes in that neighborhood were worth $50,000. They were clearly wealthy.

By 1933 the Leidy couple had patched things up with her parents. They made a trip without the children in his coupe to Palm Beach, where the Woodhouses had built another home.

It was on the return trip to Rye that Marjorie Woodhouse Proctor Leidy died, when the coupe, driven by her husband, left her hanging upside down in the mud of the Bronx River. It was 1933, and she was 30 years old. He survived to marry again, and her four children were raised by another woman.

The photo that ran in The New York Times about the accident at the Gun Hill Road bridge.

Her death merited a story in the New York Times, with the photo of the social couple, above, and a “Milestones” in “Time” magazine.

It was a blow to her parents, of course, but there had already been another blow, one that led Lorenzo to retire from the bank, and for them to flee Vermont. It was a court case that went against them, and that alienated them from their other child, C. Douglas Woodhouse.

Their son was much older than his sister. Tall, blue-eyed, he did not seem to like working much. When the draft for WWI found him in East Hampton, he claimed he worked as a teller in his father’s bank in Burlington, VT. The war office in Vermont nonetheless enlisted him in their ranks. He still managed, during training as a lieutenant in the signal corps, to make a tragic marriage to a Burlington girl that led to what the court record refers to as a criminal operation.

But you will read about that in Part II

Meanwhile, Leslie Reingold is the other exclusive sales representative at Sotheby’s.

She says the Playhouse will definitely find a buyer. There are certain people who are attracted to historic homes. They are, she says, “people with a more Italian, French, even British perspective. They are going to love this house.”

Even before the house went on the market, she says, two people already had their eyes on it.

One problem was figuring out a price. Because Richard Brockman inherited the Playhouse from his father, it has not been on the market for 60 years. In real estate parlance it is an unknown, Reingold said. unlike houses that have traded hands over the decades. How do you put a price on such a place? There is no comparable.

Reingold said the house needs a buyer who has “a love and a passion for historic homes.”

And then, in addition, that buyer will get the pool, the beach, downtown East Hampton.

The gunite pool.

“Many things have been updated,” she said. “But other things can be updated.”

Still, for $17.5 million, some buyers want a view of the ocean, even if you have to stand on your tiptoes. (Despite the warnings that someday that house may be in the ocean.)

Updated bathrooms — five of them (Sotheby’s)

So, your choice. Hampton’s history. Elizabethan charm. Downton Abbey. Just plain unusual?

“There is nothing else like it,” Shea says.