The Parrish Art Museum Is Su Casa

By Katlean de Monchy–

If you missed the Hispanic Heritage Month kick-off at the Parrish Art Museum, well FOMO. You did. You missed a vibrant soirée. On August 31, the Parrish teamed up with the We Are All Human Foundation to throw a cultural celebration that was as colorful as the art by and about Annette Nancarrow, which was on display.

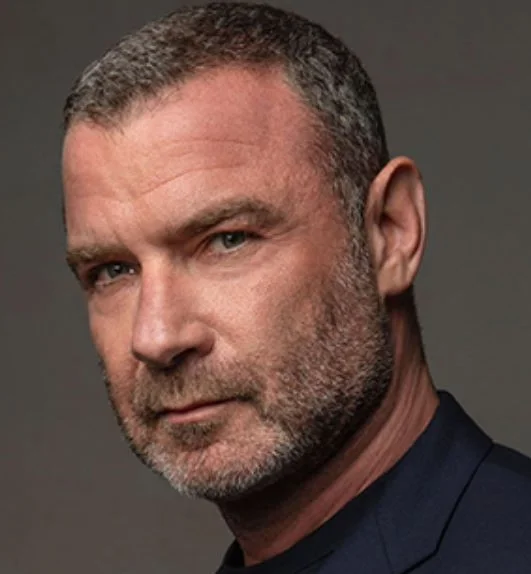

Guest at the Parrish admiring a Sandor Klein portrait of a young Annette (Painting courtesy of Bret Stephens; photo by Sabrina Steck/BFA.com)

Nancarrow was a trailblazing American, who moved to Mexico City in the mid-1930’s, fleeing a marriage to a New York lawyer. In doing so, she lost custody of her daughter, Cherry Pepper. But she fell in love with the handsome textile manufacturer Louis Stephens. They married, had two sons, Luis and Charles, and mingled with artist icons like Mexico’s “big three” — Diego Rivera, David Alfaro Siqueiros, and José Clemente Orozco as well as Frida Kahlo, Nancarrow’s lifelong friend.

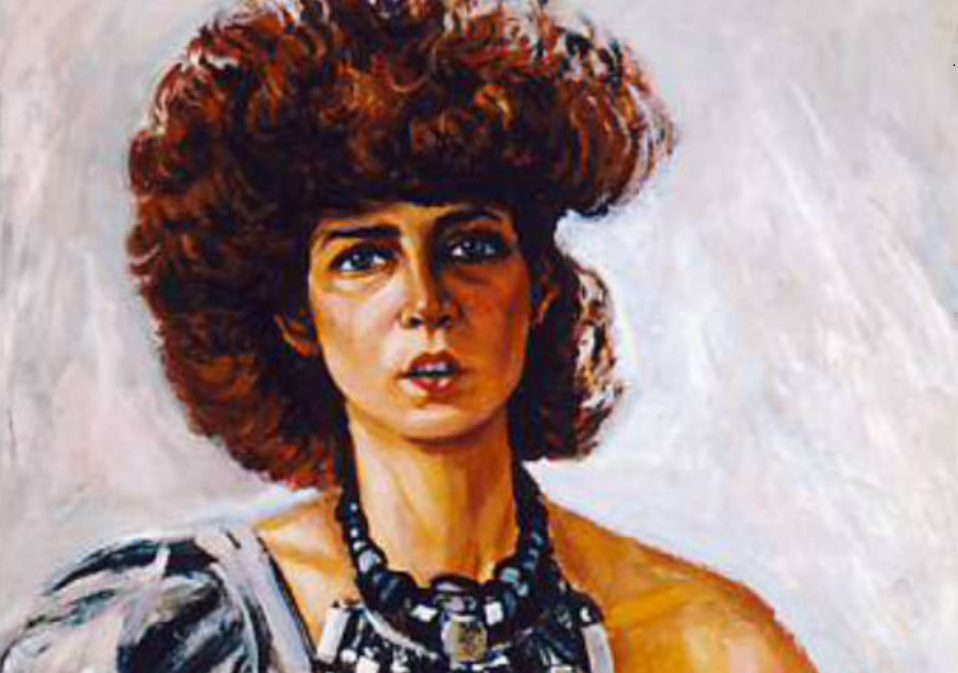

José Clemente Orozco’s portrait of Annette Stephens, as she was then known.

Louis and Annette Stephens were known for their lively salon, which included Francisco Zúñiga, Miguel Covarrubias, Federico Cantu, Raul Anguiano, and a free-flowing international crowd of writers, actors, musicians and others who joined this salon of post-Revolution free spirits.

A photo of Annette Stephens with Orozco while she was sitting for the portrait (Courtesy Rosemary Carstens’ serialized biography of Nancarrow)

Annette herself had grown up wealthy in New York and gone to Hunter College. She may have seemed bohemian, but she used interior designers to furnish her homes. She was fun, vivacious, charismatic and she had taste. She bought Picasso’s “The Frugal Repast” print when she was 16. (There were 250 made in 1913; one recently sold for $6 million.)

After divorcing Stephens, she married Conlon Nancarrow, a modern composer, and through him met a new cadre of creative people, including, on one visit to New York, John Cage, Virgil Thompson, Elliott Carter, and Aaron Copland. She knew Peggy Guggenheim, Norman Mailer. There seemed to be no end to the people who came to Mexico City and her living room, including her later home in Acapulco.

The audience at the Parrish. (Photo by Sabrina Steck/BFA.com)

Some of her work, from intimate charcoal sketches to bold sculptures, is in the hands of her grandsons Mitchell Kaneff (son of Cherry Pepper Kaneff) and Bret Louis Stephens (son of Luis Stephens), the stars of the evening. They brought paintings, sketches and images to the soirée, where they shared stories about her.

Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, executive director of the Parrish, Bret Stephens, Mitchell Kaneff, and Claudia Romo Edelman (Photo Sabrina Steck/BFA.com)

The night wasn’t just about ogling art. It was an intellectual exercise, with a panel that also featured Claudia Romo Edelman of the We Are All Human Foundation, and the Parrish Museum’s Executive Director Dr. Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, who was born in Mexico City. The discussion swirled around the impact of Latin culture on the arts—the spicy, creative cross-pollination of the 1940s and ’50s that made Mexico City an art capital.

.

A painting by Annette Nancarrow; not part of the evening. It is in the collection at the National Museum of Women in the Art in Washington DC.

Nancarrow not only spent time with famous artists, she became an agent for them, handling some of their sales and taking artworks as a commission. She worked on Orozco’s “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse” mural, and, in 1947, when she was Annette Nancarrow, she finally had a solo show in a major gallery. It was difficult for female artists, including Kahlo, in the male-dominated art world in Mexico, just as it was in the United States.

Bertha Gonzalez Nieves, Mónica Ramírez-Montagut, Claudia Edelman, Katlean de Monchy, Angelica Fuentes (Photo Sabrina Steck/BFA.com)

Dr. Mónica Ramírez-Montagut was energized by hosting the event. “It’s all about celebrating our cultures coming together and making everyone feel seen,” she said. Bret Stephens chimed in, “You can’t truly appreciate American art without recognizing the influence of Mexican culture.”

Claudia Romo Edelman, of the foundation, which advocates for equity and diversity, noted that by 2060, one in four people in the U.S. will have Latino heritage. She reminded us that Latinos have been shaping the country for centuries. Art, she said, is the perfect way to keep that story in mind.

Annette Nancarrow with Diego Rivera, a towering figure in art in Mexico (Courtesy of Rosemary Carstens serialized biography of Nancarrow)

Then again, it is worth remembering that Annette Nancarrow was considered a Mexican artist, but she was Jewish, and born in New York. That many citizens with long histories in Brazil are of Italian, Portuguese and German descent. That many Chinese settled in Paraguay, Argentina and Brazil. Pinochet was French Breton Basque. The Allende family is Spanish. Gabriel Boric, the President of Chile is of Croatian descent.

All of them, if they came to the United States, would count as “Hispanic,” because they come from Latin America.

Claudia Edelman (photo Sabrina Steck/BFA.com)

The night at the Parrish would not have been complete without the support of the art institute’s fabulous trustees and the sponsors, from Angélica Fuentes to Casa Dragones. Co-chairs included Claudia and Richard Edelman, Justine and John Leguizamo, and Bret Stephens.

The Parrish and We Are All Human want to build a community where Hispanic and Latino artists are celebrated. There will be an outdoor screening on the Parrish lawn, in collaboration with Cinema Tropical, of the 1968 film “The Batwoman” “La Mujer Murciélago” with subtitles on September 27.

Something to look forward to: December 12—the We Are All Human Gala at Cipriani. For tickets and to support these efforts go here or go to the Parrish Museum to make a donation.